CANADIANS DEAL WITH RACISM IN A DIVERSE SOCIETY.

By Queenie Affainie

Every day, Yolisa Galamba’s son makes his way home from school. He may walk alone, he may walk with his friends. But if he is with his friends, says Galamba, the nine-year-old boy risks attracting attention, unwanted police attention. A cop will stop them, ask for their names, where they’re going and then let them continue on their way. “Just being young, black men,” she says, is enough to risk being stopped and questioned.

Toronto’s Finch-Bathurst area, where Galamba lives with her son, is located next to the Jane and Finch neighbourhood, where her son attended school. A neighbourhood known—some would say it is notorious—for its gangs and guns. And while many mothers in the area are worried about that, they are equally worried about the harm that might come to their children from the people who are meant to protect them, people part of a system that has failed them.

Diversity is ingrained in Canada’s core values. Ever since the first Prime Minister Trudeau adopted it as official policy in 1971, multiculturalism has been celebrated in school textbooks, public radio and television and city festivals. Social inclusion is what Canada is about, or is supposed to be anyway. Despite the promise of multiculturalism, however, social divisions keep cropping up. But they do so often in less explicit ways than before, ways that can be harder to label as discriminatory but can make people feel as isolated as any racial epithet or sign indicating that only whites can drink from this fountain. They do so because of what many black activists and scholars call institutionalized racism.

One key way institutionalized racism works is by criminalizing certain populations. Even though there is no evidence to suggest that visible minorities commit proportionately more crimes, they are more likely than white people to go to prison. And, they get sent there at younger ages. According to Statistics Canada, 26 per cent of people incarcerated across the country in 2016 were Indigenous, even though Indigenous people are only 4.9 per cent of the total population.

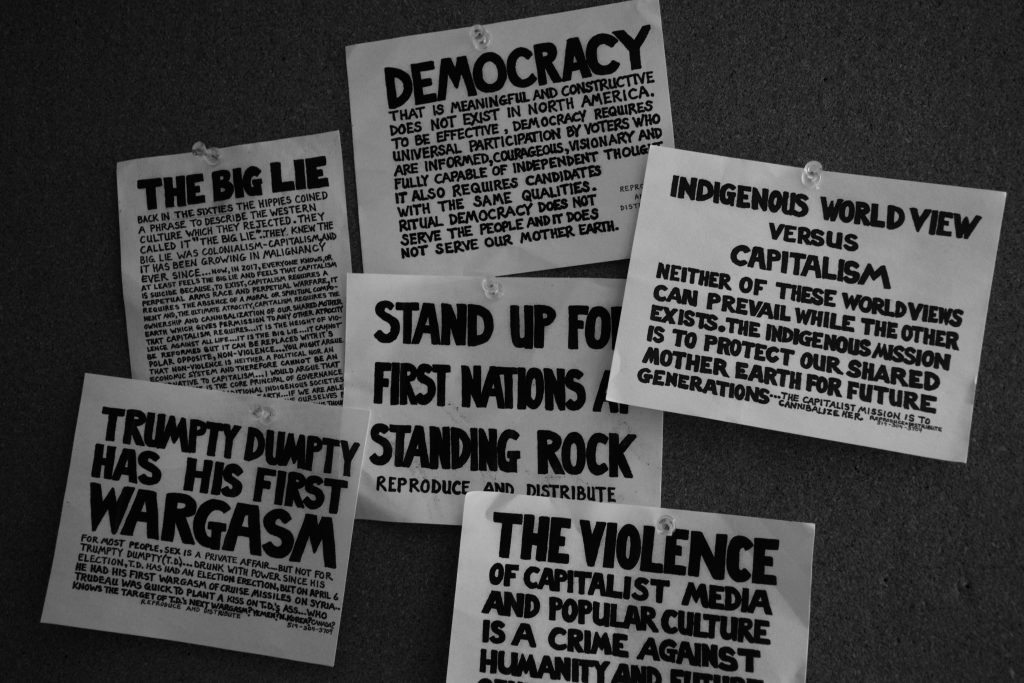

Criminalization of visible minorities is reinforced by the media. Hidayah Hassan recalls that, growing up on Falstaff Avenue, in the Jane-Finch area, the only news about black people was bad news. Almost every day she saw a story about a black youth who had been shot. On occasion she knew them personally. But the takeaway message from such news coverage was not that black people are victims. It was that they are criminals. “Sometimes I thought that the media was designed to basically have only black news. I feel like it teaches young black people that all we are good at is committing crimes, robbing stuff,” says Hassan. “If you grow up in that kind of environment, all you see is that, ‘Oh, it’s absolutely normal for me to go to jail.’”

This is how institutionalized racism works. The idea that visible minorities are in some way different, less capable, more dangerous than whites slowly seeps into people’s everyday reality. It supports existing prejudices without being noticeable.

Even the age-old practice of racial segregation exists behind the scenes today in Canada. We see it in the legacy of the reservation system. The Indian Act, which served as a model for the Apartheid-era South African state, separated Indigenous communities from the rest of the Canadian population. While there is no longer an official “pass system,” whereby Indigenous people were required to show identity cards when they left the reserves, many living on reserves today endure a different type of segregation, one imposed by poverty, substandard housing, unclean water and a lack of access to fresh groceries. For Galamba, this is not all that different from how things were in Apartheid South Africa, where she lived for 20 years. It was a system that, she says, “considered you less than human.” Referring to the ongoing economic segregation, she adds, “Apartheid is still very much alive in South Africa and certainly still very much alive here in Canada.” Multiculturalism, she says, is more of a smokescreen for racism than a way of integrating people.

The prevalence of institutionalized racism doesn’t mean other, more explicit, forms of racism don’t also exist. It may, in fact, make them more likely. According to Statistics Canada, Canada has experienced a rise in hate crimes. From 2014 to 2016, hate crimes climbed by 8.8 per cent. Racially motivated crimes specifically climbed by nine per cent.

Hassan, a Muslim who wears a headscarf, is all too familiar with overt racism. Passersby have called her the n-word and told her to go back to her country. “For me, I’m not here to babysit nobody, and I’m not going to ask them to understand me,” she says. “It’s their job to get to know people and respect them as they come.”