STUDENTS ACROSS ONTARIO AREN’T LEARNING HOW TO MANAGE THEIR FINANCES AND FUTURE DEBT.

By Hyrra Chughtai

Loud giggles echo through the multi-purpose room of the students’ union building at Wilfrid Laurier University’s Brantford, Ont., campus. A group of friends surrounds a small table, discussing their classes and co-ordinating their schedules. Aiden Legault in the centre, his planner open on his laptop, blocking out space for free time. In a crowd, Legault is usually the attentive one. He listens deeply and knows the right time to chime in with a joke. This sometimes surprises people, given Legault’s appearance—dressed in black from head to toe, with black nail polish.

Legault plans his week strategically, making sure he maximizes each day he commutes to campus from Innerkip, Ont., balancing out his classes with study time and a part-time job. It’s never an easy balance to achieve, made harder by how expensive gas and tuition are. Plus, for the first time this year, his school costs weren’t entirely covered by his student loans, which has stressed him out. He’s learning through trial and error on how to manage his finances and save enough to cover his costs. “A lot of my friends, they talk about how they do their budgeting and finance, and I’m like, ‘Wow, I wish I had those skills,” says Legault.

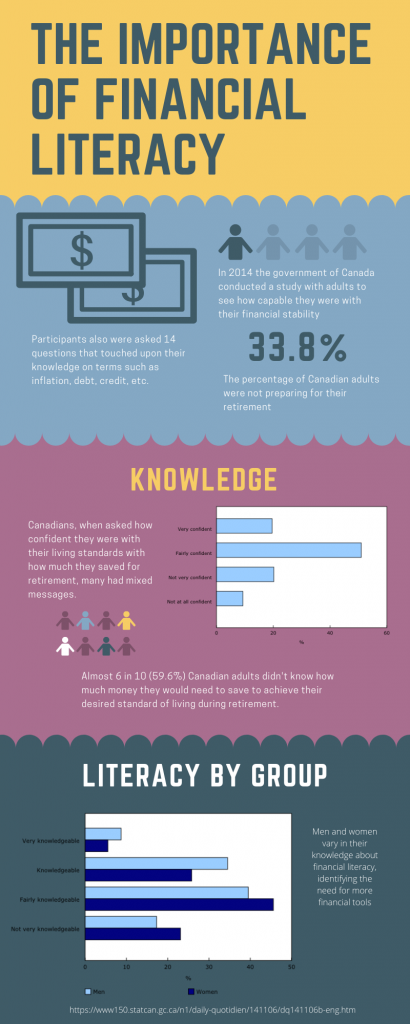

Like most students, Legault came to university with little idea of how to manage his finances—and that’s a problem. At a time when tuition and student debt loads are higher than ever, students who don’t understand how to take charge of their finances begin their lives as adults with little or no prior knowledge of how to do that. Schools need to do a better job of teaching students how to manage their money and their debt in order to set up them up for a successful future.

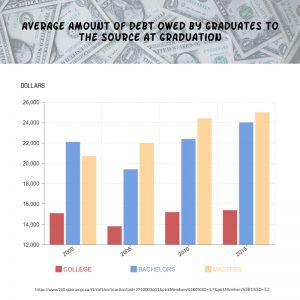

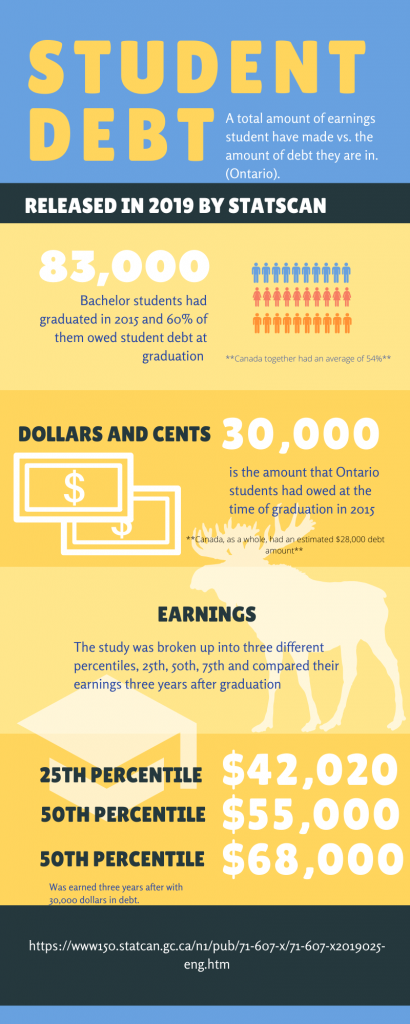

Tuition costs more today than ever before. According to Statistics Canada, in 2010, the average Ontario undergraduate paid $5,146 per year. A decade later, the average Ontario undergraduate pays $6,463 a year for full-time studies. Students in this province have relied on the Ontario Student Assistance Program (OSAP) since 1965 to help them pay for their education. In 2019, the Ford government made a number of changes to the program, including reducing the number of grants and bursaries available. According to the OSAP website, students’ expected contribution to their education has increased from $3,000 to $3,600. The amount of OSAP aid students are able to receive also depends on their parents’ income. If a student’s parents have an income of less than $40,000 a year, the amount of OSAP they are eligible to receive would be about $10,000 more than someone whose parents make more than $100,000 a year and who only receives about $7,000, according to the online OSAP calculator.

That means many students have to look at other, often costlier, options to cover their tuition and make ends meet. “I find there are a lot of customers that aren’t able to get OSAP now or aren’t able to get as much, so they are coming in trying to get student lines of credit or something similar,” says Spencer Mogridge, a TD Financial adviser in Brantford. “I’m finding it’s becoming not just harder for students but harder for their families as well because that obligation becomes a family member.”

When Legault found out about the cuts, he wasn’t thrilled—and neither were his parents. When he realized his OSAP loans would no longer cover the full cost of his tuition, he had to use more of his own savings and ask his parents for help. He also tries to pick up more shifts at Rogers, where he works for minimum wage to cover the cost of important international opportunities associated with his program. As a third-year human rights and human diversity student, Legault wants to take every opportunity he can to learn about different cultures and gain international experience. Last year, he took part in a Mexico field course to learn about migration. This summer, he was accepted for an internship in Ghana, but that comes with added costs, too. He says he’s better at managing his money than he used to be but would still like to learn more.

Abby Myles understands, admitting she spent too much money on fast food and unnecessary clothes when she started school. “The way I budgeted in first year was very different than the way I budgeted in fourth year because I figured out more of the things that I need rather than the things I want and how to balance those,” says Myles, a human rights master’s student at the University of Manitoba, in Winnipeg. Through trial and error, she eventually learned how to budget.

Most university students don’t know anything about how to manage their money. “It’s not their fault. It’s everybody else’s fault and the parents, too,” says Laura Allan, executive director of the Schlegel Centre for Entrepreneurship and Social Innovation and assistant professor of business at Wilfrid Laurier University’s campus in Waterloo, Ont. She says the high school system doesn’t teach students how to be financially responsible, so they’re left to figure it out on their own. But it doesn’t have to be that way. At Laurier Brantford, for example, most students take four foundations courses, which instruct them on academic literary and integrity and how to conduct research and write essays. Financial literacy should receive the same attention. “If they have one foundation course on how to manage money, that would be pretty helpful,” says Legault.

Laurier offers a Dollars and Sense program, which is a series of workshops on a variety of financial topics that students may choose to attend. They provide resources to ensure students know where to go for help but beyond that, it’s all up to the student.

Currently, Legault is trying his best to bulk up his savings. With the Ghana internship coming up in May, picking up more hours at Rogers seems more sensible than spending extra time elsewhere. Creating the balance among home life, work, friends and school is something that Legault will continue to learn. Along with gaining more financial knowledge, it will be a long learning curve.