WITHOUT PHYSICAL AND SOCIAL SUPPORTS, LOSING A LIMB CAN LEAD TO SOCIAL ISOLATION.

By Savannah Dale

Scott Sackaney, a 23-year-old double amputee from Brantford, Ont., was at a local pool bar with friends one night when a man stumbled over to them. As Sackaney recalls, “he looked at me and said, ‘Oh, what the fuck happened to your arm?’” One thing led to another and a fight broke out between them, sending one of Sackaney’s teeth flying. A couple days later, he started to feel the effects of the fight. In particular, the injuries to his lower residual limb laid him up for almost three weeks. During that time, he was practically wheelchair bound—an outcome that had both physical and psychological effects. As he explains, “there were a couple get-togethers, and my friends went out to play some pool, but I couldn’t go. Well, I could have. It’s just, you know, I didn’t want to go in my wheelchair. I didn’t want to be a burden. I didn’t want to feel like that.”

As Sackaney and countless others have learned, the process of overcoming an amputation doesn’t end when the skin has healed. For many amputees, the journey only then begins. Learning to live with an amputation can be a long, difficult and socially isolating journey. But with a strong support system in place, it is possible for amputees to get their lives back on track.

According to Bita Imam, a researcher at the University of British Columbia, in Vancouver, the number of lower limb amputations in Canada is unknown. While several countries collect this sort of data, Canada has yet to follow suit. However, many experts say that as the diabetes epidemic grows, so does the number of amputations because diabetes decreases blood flow and can cause health complications that result in amputations. To get an idea of what those rates may look like, consider the following facts provided by the Diabetes Canada: in 2016, there were more than 1.6 million people in Ontario living with diabetes. Every four hours, there’s one amputation in Ontario resulting from a diabetic foot ulcer. Of course, not all amputations are associated with diabetes; the reasons why a person may undergo the surgery vary significantly, from cardiovascular disease to a traumatic accident. Despite the reason, the loss of a limb is life-changing.

As new amputees begin to recover from surgery, many look forward to getting their life back on track with the aid of a prosthesis, an artificial extension that replaces a missing body part, commonly an arm or leg. It is worn on the remaining portion of the limb, and the degree of independence it can offer amputees is significant. Yet, it comes at a price that not everyone can afford.

The price of mobility isn’t something most able-bodied people give much thought to, but for many amputees, it’s top of mind. This is because prostheses and other accessibility modifications aren’t fully funded by government health plans. For example, Ontario’s Assisted Devices Program will make a maximum contribution of 75 per cent toward the purchase of “the most basic” prostheses. As Jesse Cornell, a certified prosthetist at BioDesign Prosthetics & Orthotics, in Brantford, Ont., puts it, “the ADP feels that a $500 foot should meet the needs of everybody out there, whether it be a young, active individual or an older geriatric that tends to sit a little bit more.” And even if the ADP grants its maximum contribution, the amputee is left to cover 25 per cent of the remaining cost. For people who don’t have additional insurance or who rely on pension payments, finding funding is a challenge, says Cornell.

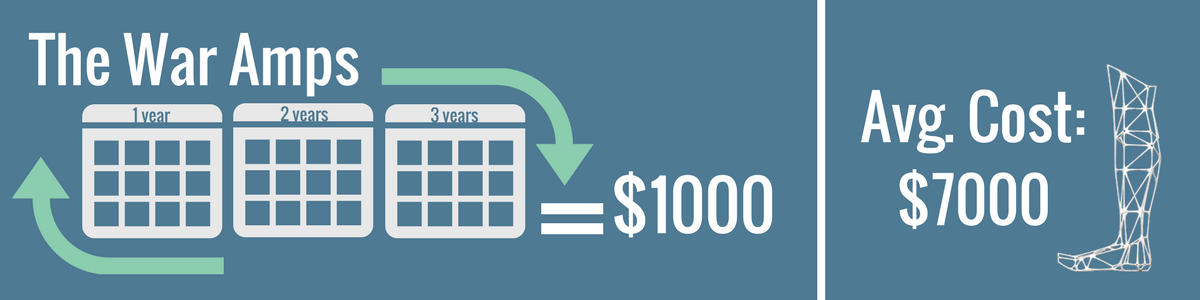

Charitable organizations can help lessen the financial burden but accessing their funds can be a lengthy process, and amputees must meet their criteria to qualify and receive help. For example, The War Amps typically grants eligible applicants about $1,000 every three years toward a new prosthesis. But as Cornell notes, the average cost of a below-knee prosthesis is $7,000. March of Dimes helps people with a range of physical disabilities modify their homes and vehicles for easier accessibility. Unfortunately, the program is heavily oversubscribed. “We receive $9.2 million a year in direct funding. If we were to examine the current demand on the program, we would be in the ballpark of $30 million,” says Anita McKinlay, team lead of the organization’s Barrier Free Design Consultation, in Toronto. Amputees who are either ineligible for, or have exhausted all possible avenues of, financial assistance and still can’t afford a prosthesis or accessibility modification may have a harder time leaving their homes and getting out into their communities. This can lead to a variety of problems, including a sense of social isolation. As one might imagine, the challenges don’t end there.

After an amputation, the residual limb is susceptible to wound pain. While the suture line is healing, amputees must be careful to avoid putting too much pressure on it. Even when it appears to be healed, and the surgeon gives the go-ahead to start wearing a prosthesis, it’s essential to stick to a proper wear schedule. But the reality is that many amputees push themselves in an attempt to get back into the swing of things. Kyle Goettl, nurse clinician for the regional rehabilitation program at Parkwood Institute, in London, Ont., says this is especially true for young men. “They push their way. They’re recommended to wear their prosthetic a certain way or for a certain length of time and to monitor regularly, but life gets in the way or they just think they can do more because of their age,” he says.

When it comes to wound care, Goettl says that where amputees live can affect the quality of their treatment. For example, he says London is the only city in the South West Local Health Integration Network offering electrical stimulation, a treatment that helps wounds heal faster. If a wound doesn’t heal quickly or properly, amputees become unable to walk on their prosthesis due to pain, which may restrict their mobility and how active they can be. Despite the significance of the physical pain most amputees experience early on, it’s impossible to understand the challenges involved in the recovery journey without taking into consideration the psychological struggles as well.

The Amputee Coalition, an American non-profit, reports that as many as half of all amputees will need some type of mental health service. Research shows that it’s common for amputees to feel depressed or have suicidal thoughts. In studies, many amputees say they feel like a burden on their loved ones. Whether this burden is real or merely perceived, it can be enough to make amputees isolate themselves. Others report often feeling frustrated, as they find themselves unable to do something that they were once able to. A Seattle-based study shows that amputees may also feel self-conscious. People who feel this way acknowledge avoiding certain physical activities because they don’t want others to see their prosthesis or residual limb. Amputees who lack the self-confidence to perform physical activity may be less willing to try new activities. This, in turn, could affect how much they leave the house and interact with others, which could lead to a growing sense of isolation.

Despite the challenges amputees face, many of them are able to recover. Brenda Schedler, of Wingham, Ont., is a left, below-knee amputee who credits her friends, family, church community and recreation specialist for supporting her during her recovery. As someone who’s always been independent, she says having to rely on others can be frustrating. This was especially true immediately following her amputation when she was awaiting her prosthesis. Without these people, says Schedler, she probably wouldn’t have gone out in the community as often as she did because manoeuvring outdoor stairs on her own is a struggle. One of her supports is a fellow amputee who reaches out to her to ask if there’s anything she needs or wants to talk about. “He’s kind of an inspiration,” she says. “It’s nice to have someone else that you know who’s done so well, to look at and think, ‘OK, well, maybe I can do some of those things.’”

That kind of support from friends and family is crucial. Barbara King, of Caledon, Ont., was a right, below-knee amputee who died in 2005. Her granddaughter Victoria Dodds says King struggled for about a year and a half to find a prosthesis that fit without rubbing or irritating her skin to the point of infection. That could have kept her confined to her home, but that wasn’t the case, thanks to the support of her family and friends. Dodds says King didn’t always have the best relationship with her children as they were growing up, but she believes the amputation brought them closer. “She was a very independent person, and it was the first time that she really needed to rely on them,” and they were there for her, says Dodds. King also relied on the support of her church community, who encouraged her to continue attending their services and events. Dodds remembers how the church would sometimes hold functions in the basement. These events were difficult for King to get to because the church was not fully accessible to people with physical disabilities. But Dodds remembers a time when a fellow church member carried her grandmother down the stairs so she could attend an event there.

Remaining socially active after an amputation can be challenging. Sackaney lost his right arm and leg in a railway accident. Before the accident, he was busy, heavily involved in martial arts and, like many high school students, spent a lot of time with his friends. After the accident, he became depressed because of what had happened and because he was wheelchair-bound for about four months before getting a prosthesis. “I thought about suicide. I never actually attempted it, but I always thought about it,” recalls Sackaney. “I was pushing all of my loved ones away and all of my close friends. It was a pretty rough time.” Despite those dark times, he says he’s thankful for his supportive friends, who never take no for an answer. Sometimes in the summer, “they’ll leave my leg in the truck and carry me out to a kayak,” says Sackaney. “What we’ll do is have a piece of rope and we’ll attach it to the front of my kayak and the back of theirs so they can tow me along the river. It’s pretty nice.” That’s why having a strong support system in place is crucial for amputees. Take it from Sackaney. “If it weren’t for all the supportive people around me, I don’t know where I’d be right now,” he says. And then he reconsiders. “Actually, probably down in the gutter somewhere.”