NINETY-MINUTE BUS RIDES, BROKEN EQUIPMENT, FLEEING STUDENTS: FRANCOPHONE EDUCATION IN ONTARIO IS BROKEN AND THE PROBLEM WON’T FIX ITSELF

By Gabrielle Lantaigne

Sébastien Lalonde still recalls the awe he felt when he stepped into Brantford Collegiate Institute. What he saw was an everyday occurrence for students of that school and many like it, but for Lalonde, it was shocking.

In the summer of 2014, the 18 year old was gearing up to begin his first year at York University in Toronto. Before leaving his hometown of Brantford, Ont., though, he had some business to take care of — Lalonde was a student trustee for the Conseil scolaire de district catholique centre-sud (now Conseil scolaire catholique MonAvenir), one of Ontario’s French-language school boards, and had been tasked with visiting other area high schools.

As a proud student of Académie catholique Mère-Teresa (ACMT), Lalonde couldn’t believe how local English high schools contrasted with the little French Hamilton high school from which he had recently graduated.

Where his school barely fit on its land, the English schools had space to spare. Where his school could barely offer sports teams, the English schools had dozens.

“It was something that I could only dream of having in my own high school experience,” he said.

Not much has changed since then.

Julia Baverstock, 17, a current student at ACMT, said the school is still struggling.

“My teachers are doing the best they can with what they’ve been provided,” she said. “Half of our projectors don’t work, and it’s always a struggle for our teachers to show us the PowerPoint or the lesson plan when it’s on their computer.”

In winter, Baverstock said, only half of the school building gets heat. In the time that I was a student there, lead leached from the pipes, forcing the school to shut down drinking fountains for a number of weeks.

Across Ontario, francophone students say they’re getting the short end of the educational stick — struggling with crumbling buildings and poor technology — issues that many students in the English school system don’t face. Some students are so frustrated they’ve switched from the French to the English school board.

Danielle Frenette, 17, attended a French elementary school in Hamilton before switching to an English high school. After completing Grade 9 at Bishop Ryan Catholic Secondary School, she transferred to ACMT, returning to the friends and the community she had grown up with. She said what she saw at Bishop Ryan was worlds away from what is available at ACMT.

“There was a flat-screen television in every single classroom,” she said. “The library was pretty much the size of our school in itself.”

Many English schools in Hamilton have had major renovations or new buildings built over the past few years. In the eyes of Hamilton’s francophone population, this only seems to widen the gap.

“Even looking at the old English schools that eventually get renovated like Bishop Ryan, the old ones don’t even compare to what we have,” said Frenette. “So even our school now, today, still is not as nice as the old versions of other English schools.”

Although this may sound like a case of students seeing greener grass on the other side, even those in charge have noticed the difference.

“Particularly in Hamilton, you’re not comparing apples with apples,” said André Blais, director of education at Conseil scolaire catholique MonAvenir. “You’re comparing apples with a grapefruit.”

Stories like these are repeated in French-language schools across the province. This leaves many feeling that French-language schools in Ontario don’t have the same basics as most English-language schools. In what’s supposed to be a publicly funded education system, why is there a two-tier structure — one that puts francophone students at a disadvantage?

In 2014, Blais’ school board was the first French-language board ever to file a lawsuit against the government of Ontario for a new school building. The lawsuit was filed after what the board referred to as “decades of inaction” on the part of the provincial government. They argued that ACMT was housed in a building that had been problematic since the beginning.

One concern was the size of the site: while the standard area for high schools in Ontario is between 10 and 15 acres, ACMT is located on less than an acre. The building occupies almost the entire site, meaning students don’t have access to a sports field or schoolyard.

The board said the building, initially intended as an elementary school, was only supposed to be a temporary home for ACMT. But nearly 20 years later, ACMT still sits on the same piece of land.

The lawsuit was placed on hold, and Blais says a new school is in the planning stages, but it has not yet been built.

Promises unfulfilled

In November, Premier Doug Ford announced the province was cancelling plans for its first French-language university, the l’Université de l’Ontario français, despite the fact that support for the university was a campaign promise. Even more alarming, the premier announced the province would cut the French Language Services Commissioner, which many consider the only independent watchdog for francophone rights. Its responsibilities would be transferred to the Ontario Ombudsman.

Ford’s disregard for the rights of hundreds of thousands of francophones living in this province has not come out of nowhere. It’s part of a history of Franco-Ontarians being pushed aside, ignored and marginalized.

In 1912, the provincial Conservative government passed Regulation 17. Although most Ontarians have no idea what that means, ask any Franco-Ontarian about le règlement 17 and they will tell you that it made French-language instruction illegal in Ontario schools. It was amended the following year after vehement reaction from the francophone community, but the government refused to fund French-language high schools until the late 1960s.

Just as the community fought then, many francophones have protested Ford’s recent decisions.

When it comes to the backlash against government cuts, though, Conservative MPP Gila Martow believes some protesters may be hurting their own cause.

Martow, parliamentary assistant to Minister of Francophone Affairs Caroline Mulroney, said she once proposed a francophone hub in downtown Toronto that would include a tourism office with services in French, a bilingual coffee shop, small museum, French films and a screen displaying francophone facts and translations of common phrases.

“I’m yammering about all of this in French, and Giles Bisson yells out from the NDP . . . ‘They’re not asking for a restaurant, they’re asking for a university!’ So that’s all they tweeted, all the students,” said Martow.

“It’s defeating their own cause, because what’s the real point here? The real point is to get some French flavour and to improve the whole idea that French is a language spoken in Ontario that too many people in Toronto forget.”

One might argue that the “real point” is to uphold constitutional rights by giving equal access to education rather than getting some “French flavour” in downtown Toronto.

Under Section 23 of the Charter, minority official language speakers are guaranteed the right to educate their children in their own language. This gives French speakers the right to French-language education in English-speaking areas.

Much of the outrage over Ford’s decision comes from the fact that although francophone students in Ontario are guaranteed elementary and high school education in French, the province doesn’t have a single full-French university.

There are two francophone colleges (La Cité collégiale in Ottawa and Collège Boréal, with campuses across the province) and four bilingual universities: Royal Military College of Canada in Kingston, Sudbury’s Laurentian University, the University of Ottawa and Dominican University College (also in Ottawa). York University has a bilingual federated college, Glendon, but the institution is otherwise anglophone.

Many francophones, like Florence Ngenzebuhoro, don’t feel that a bilingual university is equivalent to a francophone one.

Ngenzebuhoro, executive director of the Centre francophone de Toronto and a member of the board of governors of l’Université de l’Ontario français, attended Laurentian. It was not the same as a full-French university, she said, because the quality of spoken and written French wasn’t up to par and she was still surrounded by English-speakers when not in class.

Martow believes the francophone university was set up to fail. She says the Liberals pledged to go ahead with the university just before an election, when they were “desperate to try to please every stakeholder that they ever met in 15 years by promising everybody everything.” These promises included expansions for universities like York and Wilfrid Laurier, which Ford also cut.

“We couldn’t cancel some university expansions and go ahead with others,” said Martow.

Blais disagrees.

“The difference is, we don’t have one and they have many,” he said. “Our realities are completely different.”

Students like Baverstock, who is preparing to graduate high school, were disappointed with the announcement.

“If I want to get a French education, I don’t feel like I should have to go all the way to Sudbury or Ottawa or Québec…” she said.

Distance is certainly an issue for many young francophones when it comes to accessing education in their own language. Some cannot afford to live away from their families.

L’Université de l’Ontario français would have given the substantial percentage of Franco-Ontarian youth living in central and southern Ontario the opportunity to study in French close to home.

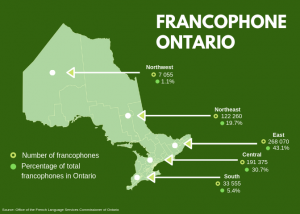

And those numbers are growing as Ontario welcomes immigration, specifically francophone immigration, said Yves-Gérard Méhou-Loko, senior investigator at the office of Ontario’s Commissioner of French Language Services.

“We know that people are settling in this part of the province, so we need to offer them a proper post-secondary education and the access to that of course,” he said.

The government said cutting the university was simply a financial decision, made because Ontario is $312 billion in debt.

Francophones were not satisfied with that answer. In the weeks following Ford’s announcement, hundreds of thousands across the province protested the cuts.

“There’s a way to do things in a positive way and get better results sometimes than just sort of complaining,” said Martow. “Complaining or even demanding, it all has its place, but at the end of the day, I think you’re always better off coming up with positive suggestions and compromises…”

As members of a minority that has often been left behind throughout its history, many francophones feel that demanding is the only way to be heard.

The uphill battle for preservation

Parents who enrol their children in French-language schools do so with the hope of protecting their language and culture, something that is immensely difficult to do in a minority setting.

Blais thinks that the government believes it’s being fair in its funding of the French system, but that doesn’t mean needs are being met.

“Because we are a minority, it costs more to educate the minority,” he said. “It costs more to support the minority culturally, and we may not always get that recognition.”

He believes the government needs to make a distinction between equity and fairness.

“Somewhere, somebody’s got to step up and recognize that we’re not the same and we can’t be treated in the same fashion,” said Blais.

It costs more to staff French schools because they are generally smaller but still want to offer students the same choices in subjects, he said.

Another issue is transportation. Because there are fewer French-language schools, the catchment area is much larger. This means students as young as four can sometimes travel over an hour each way just to get to and from school.

“Our schools are regional schools and not community schools or neighbourhood schools, which means that most of our kids are bussed to school,” said Blais. “You can’t apply the same funding formula for bussing for the anglophones and the francophones.”

Space is another problem. Blais says his board’s schools are bursting at the seams. Many already have the maximum number of portables allowed under city bylaws.

These issues are not unique to ACMT or the schools in Blais’ board; this is a story that is repeated in francophone minority language schools all across the country.

“We have children who basically spend from Grade 1 to Grade 6 in portables, which is not sustainable for the development of French education in Ontario,” said Méhou-Loko.

Because of that, more and more fed-up francophone students are leaving for the English-language boards, raising the specter of a dying French language and culture.

Carolyn Kelly-Ruetz, 22, was one such student. She attended a French Catholic elementary school before deciding to switch to English in high school.

For her, the course variety and extra-curriculars in the English system “outweighed getting more of a French experience,” she said.

And that’s what many francophones fear. Students will be wooed away by the opportunities English language schools can provide, eventually shrinking the French-language boards in Ontario until they disappear. Without the opportunity to learn in French, future generations may lose their language and culture completely.

“It’s so fragile,” said Ngenzebuhoro.

ACMT is limited in the clubs and extra-curriculars it offers. While I was a student, it was one of the only schools in Hamilton that didn’t have a girls’ basketball team.

Frenette, who switched briefly to the English system before shifting back, believes that ACMT’s facilities and the lack of extra-curriculars are major factors in francophone students choosing English schools, leading to a vicious cycle.

“It sort of dissuades people from coming to these schools, and then it sort of becomes a whole big loop of things, because nobody wants to come here and then we don’t get enough students and then we don’t get enough resources, so nobody wants to come here,” she said.

As an annual report from the French Language Services Commissioner lays out, the government has an obligation to “provide an educational experience that is substantively equivalent to that of the majority for the entire province.”

This experience includes the teaching environment, the academic performance of students, their extracurricular activities and the time it takes them to travel from home to school, the report concludes.

It’s clear that these obligations aren’t being met in Ontario.

“I think that we end up having to make that decision: either to subscribe to being a part of a minority and a minority culture and being comfortable with that decision, being proud of that decision, and understanding the consequences behind it, or doing the one thing that our high schools and elementary schools consistently warn us about, and that is assimilation,” said former student trustee Lalonde.

In spite of the challenges, though, francophone schools are doing a lot of things well. In 2013, the Fraser Institute, a think tank that tracks school performance, ranked ACMT’s standardized test scores as the best among high schools in Hamilton.

Students and faculty also enjoy a strong sense of community, drawn together by a common identity.

A different funding formula

What is the solution, though? How can Ontario’s educational system truly become fair and equitable for francophone students?

One suggestion is to change how French language elementary and high schools in the province are funded. Francophone schools have different needs and challenges than their anglophone counterparts. Let the funding for these schools reflect that in order to create an experience that is comparable.

And Ontario needs a central full-French university where francophone youth can continue their education in their first language close to home.

Unfortunately, neither of these is likely to happen any time soon given the province’s debt and the priorities of the premier.

In a 2005 report, the Standing Committee on Official Languages wrote that the provinces and territories are bound by section 23 of the Charter and all levels of government have an obligation to work together in the best interests of youth.

“Each delay and missed opportunity permanently compromises the future of these young people and jeopardizes the community and cultural life of all francophones in Canada,” the report said.

“A modern state should not tolerate this.”