IMMIGRANT YOUTH FACE HIGH UNEMPLOYMENT RATES, RACISM AND EXPENSIVE BUREAUCRACY IN CANADA.

By Jayden Richards

The factory job was a nightmare. Unfair tasks and constant bullying from coworkers started to take a toll on Simran Karuzz. She decided to draw the line after she was told to “go back” to India and that she was stealing a job from a Canadians. She was fed up, but her spirit never broke.

Even though she appears nervous, you can tell Karuzz has an infectious personality. Her bright smile is often on display, even though the story that she tells is heartbreaking. “My first job was just for one month, and I left that job because of racism,” she says. It’s clear that she’s a fighter who won’t rest until she’s given a fair opportunity in the Canadian workforce. “As an immigrant, people don’t want the immigrants to do the jobs. The first preference is Canadian kids. Second preference would be us.”

Difficult, expensive and isolated are the words Karuzz uses to describe living in Canada. After leaving India a few years ago because of limited job opportunities, she came to Ontario hoping to earn an education and gain experience in the workforce. The problems that she’s encountered have been horrifying. Currently enrolled at Conestoga College, in Kitchener, Ont., for business, 22-year-old Karuzz tries to balance her fight for justice and schoolwork. The process to obtain permanent residence in Canada is a tiring one. Her student visa is set to expire this year, despite the fact that she still has three semesters of school left. As the clock winds down, Karuzz is forced to scramble for solutions that will prevent her from being sent home before she can get her degree and find a job in her field.

Every year, Canada welcomes thousands of newcomer youth in search of improved job prospects and a better life. For many of them, though, it can end up feeling like a case of bait and switch, given the challenges and costs involved in becoming a permanent resident. That’s why the government should invest more resources into helping newcomer youth succeed, because we all benefit from a more internationalized workforce in terms of skills, experience and innovation.

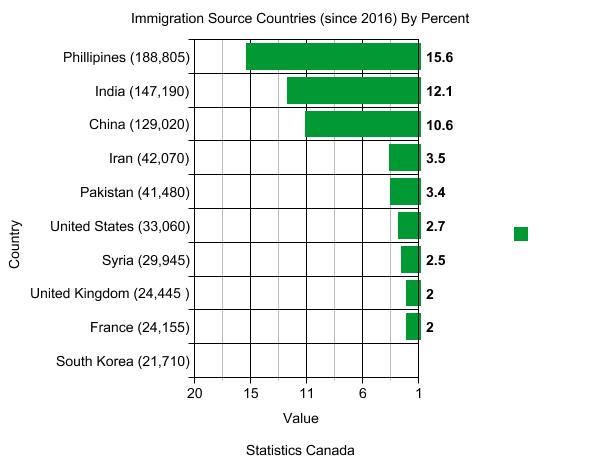

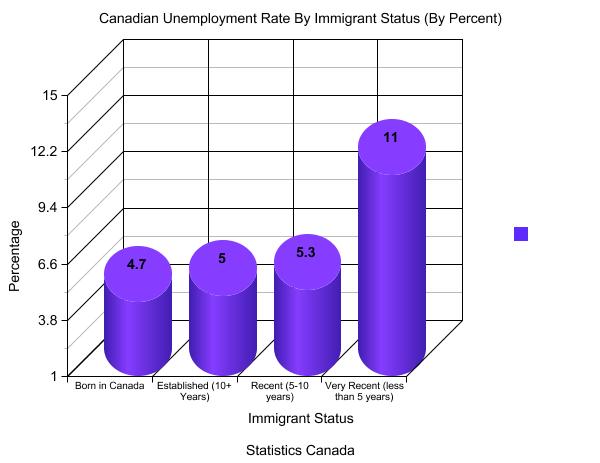

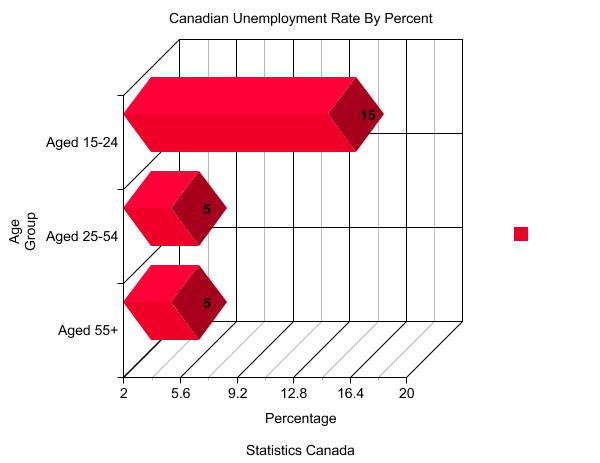

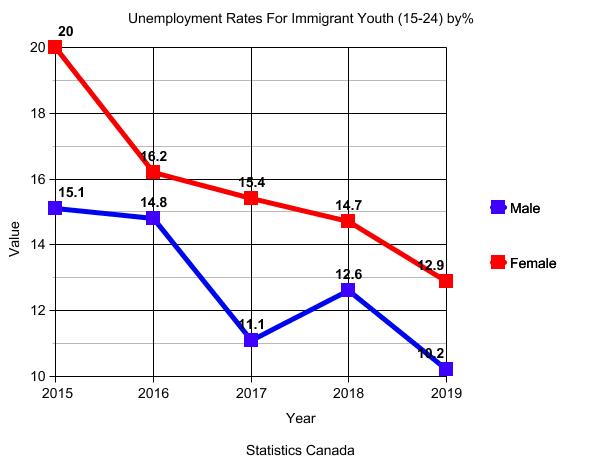

Today, the majority of newcomer youth arrive from Asia — mostly China and India –hoping to escape limited job opportunities at home. The unemployment rate for newcomer youth is quite high, though, and has been since the economic downturn of 2011, when the rate jumped to 11.5 per cent. Since then, it’s hardly moved. The unemployment rate for Canadian youth, in comparison, was 10.7 per cent in 2019.

DATA ON IMMIGRANT YOUTH IN CANADA

One reason why newcomer youth face high rates of unemployment is associated with their credentials. “There’s a discrepancy between what their education and their work experience is in their home country versus how they get credit for that in Canada,” explains Beth Pitt, program supervisor of employment services at Lutherwood, an agency in Cambridge, Ont., that provides housing, employment and mental health support. As a result, newcomers are often forced to take jobs outside of their fields of study.

These problems are the worst for newcomers who earned all of their credentials abroad. “There’s youth that immigrate and go to school and then try to get a job, which are completely different then youth that immigrate after school and try to get a job,” says Ken Jackson, an economics professor at Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo, Ont. Although youth who gain work experience and study in Canada still face discrimination, it’s worse for those with no experience here.

Another challenge newcomers face relates to networking. “When arriving to the country, recent immigrants tend not to have the same social networks in place” as those who grew up here, says Logan McLeod, chair of economics at Laurier. “That might prevent access to certain options within the labour market.” Karuzz has seen that first-hand. As part of her student visa conditions, she had to find a part-time job. After being turned down for countless positions, she found employment six months later at a Skechers store in her local mall, at which she’s succeeding. “She’s a hard worker, she takes initiative,” says manager Mohamed Hajjo. “She’s always looking to help customers and keeps a positive manner, being as polite and respectful as she can.”

This Canadian employment experience should help Karuzz obtain permanent resident status, but it’s still an uphill battle. In order to get a work visa and permanent residence in Canada, applicants must find a full-time job within a year of graduation and have a reference letter from a previous employer in Canada, for whom they worked for at least one year. She’s hopeful she’ll be able to get a letter from Skechers and is trying to remain optimistic about what she needs to accomplish — finish her diploma, find a full-time job — in the next two and a half years. She wishes the process were a little more forgiving, especially for young people like her, who are just starting their careers.

Shannon Kerr, a communications adviser with Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, in Ottawa, says the government is working to remove the barriers that newcomers face. Its Foreign Qualification Recognition and Foreign Credential Recognition programs help integrate newcomers into the labour market by verifying the skills, work experience, education and knowledge they obtained abroad and comparing them to Canadian standards. Under new regulations in the Targeted Employment Strategy for Newcomers, applicants will be able to start the process of having their credentials recognized before coming to Canada.

That makes Karuzz hopeful about her future, but for now, it’s a waiting game. “I want to enter the business world after getting my degree. I want to prove that I can accomplish anything I set my mind to,” she says.